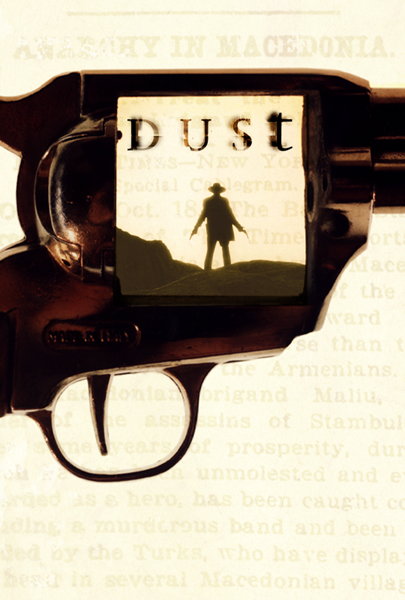

Joe Fiennes is having another bad day. While Naomi Campbell grows impatient for his company in London - and the lady is not one for waiting - he is stuck on a scorching hot Balkan mountain top, the air thick with every sort of biting and stinging insect. The brain begins to boil at about 42 degrees celsius (108 fahrenheit) - and, this morning, with forest fires raging on the horizon, the temperature is touching a barely believable 50. Joe won't be getting to London any time soon. Today, though, he gets to give his Australian co-star David Wenham a good kicking. You can hear the dull thud of boot on rib as soon as you leave the shade of the ancient Orthodox monastery of Treskovec in southern Macedonia and snake your way up through the tinder-dry alpine meadow strewn with Byzantine rubble to the baking rock of the summit. Wenham is writhing in the dust, coughing and spluttering, surrounded by a halo of wasps. Fiennes, unshaven, irritable and obviously relishing the prospect of another day stewing in his own sweat, kicks him in the stomach, grinds the heel of his cowboy boot down on Wenham's hand and drawls: ":You never were no good, Luke.": This goes on, with a short break for lunch and an adjustment of Wenham's bandages, from 9am until after 8pm. By then, even Milcho Manchevski (the man who persuaded them to ":come to Macedonia and be in my 'eastern' - it'll be fun":) has had enough. And this was one of the good days on the set of Dust, the first ":baklava western":. Even by the tortuous standards of movie-making, this was a bizarre and horrendous shoot - Apocalypse Now without the luxury of a studio budget. The omens were not good. From day one, the crew began dropping like flies from dysentery and a medical dictionary of equally nasty complaints - even the unit doctor invalided himself out. Then it got weirder. A week before I arrived, as the worst heatwave to hit the Balkans in 30 years added sunstroke to the sick list, a flock of marauding sheep, half-demented with thirst, overran the set. These being Balkan sheep, there were casualties. A few days later, several people were badly stung by thousands of wasps drawn to the watermelons bought to keep the surviving crew from expiring. The swarm was followed by plagues of mosquitoes and horse flies. Then came dark mutterings from the Macedonians on the crew of a government plot. Wasn't it strange how, as the thermometers on set screeched towards 50 degrees celsius, each night on the state TV news the temperature never topped 42 - the level above which a national emergency would have to be declared and all work stop? It was as if the film - a Cain and Abel, id versus ego, parable of two cowboy brothers from the old American west who bring their deadly filial feud to Macedonia when they enlist as mercenaries on opposing sides during the first Balkan war of 1912 - had incurred the wrath of the Almighty. If it sounds like something only Sam Peckinpah might have attempted, you'd be right. But then old Sam always claimed to have the devil on his side. Everything, including Nato, seems to have conspired against Dust and its dramatic historical sweep from the badlands of Arizona to bandit-ravaged turn-of-the-century Bitola, where the young Ataturk fought in vain to keep the Macedonia of his birth under Ottoman control. As final preparations for filming began in the spring of 1999, war broke out in neighbouring Kosovo and frightened the money away. Manchevski's pleas to be allowed to go ahead were drowned out by the roar of American B52s passing overhead on their way to pulverise Pristina. There was one other unquantifiable factor at work here almost as fiery as the weather. For, presiding over this surreal Fitzcarraldo in a huge cartoon stetson hat was the enigmatic figure of Manchevski himself, a former punk from the Macedonian capital of Skopje, who walked off the set of his last film after only a fortnight because he claimed its Hollywood producer thought ":she had a bigger dick than me":. And yes, those immortal words ":He'll never work in this town again": - or ones very like them - were indeed uttered by Laura ":Pretty Woman": Ziskin after that spectacular falling out on the cannibal flick Ravenous. (Tellingly, the crew rebelled against Manchevski's replacement and Ravenous was eventually finished by the British director Antonia Bird, who maintains that its problems were not of Manchevski's making. ":He'd been stitched up big time, in my opinion.":) Even shorn of his green mohican, Manchevski cuts quite a figure. Only someone with a highly developed sense of the ridiculous could stride on to a set in a joke cowboy hat and badass shades, with a vast pashmina shawl draped around his narrow shoulders, and expect to take charge. First impressions, of course, can be very deceptive. Manchevski may have picked up the swagger, and that eccentric dress sense, directing pop videos in America for the likes of Arrested Development, but he is no cocky fool. For he knew there was a lot more than money, or even whether he would be allowed behind a camera again, riding on Dust. ":I spent five and half years sweating blood to make this film,": he says. ":I was making a shit-load of money trying to make studio films, but I just couldn't do it. You can't make good films that mean something by remote control. You couldn't make up what happens in LA, it's beyond satire. Hollywood is full of the most miserable, unhappy people I have ever met - and I'm from the Balkans.": That little contretemps with Ziskin, arguably the most powerful woman in Hollywood, would have probably finished his career had Manchevski not had an Oscar nomination and won the Golden Lion at Venice for Before the Rain, his lyrical debut warning of what might happen if Macedonia followed the rest of the former Yugoslavia over the abyss into war. It is hard to underestimate the effect Before the Rain had on this tiny, fragile and fragmented country of 3m, with no obvious historical or ethnic precedents other than a shared reluctance from its either Slav or Albanian-speaking peoples to throw their lot in with the madhouses of Belgrade or Tirana. Macedonia - the word means ":mixed": - also has Serb, Vlach, Roma and Bulgar minorities, making it in present Balkan terms more a conundrum than a country. In such disputed circumstances, Manchevski has become, unwittingly and unwillingly, more national talisman than mere film-maker. His perfectionism may make him a nightmare to work with at times, but in a country where cliques and political cabals hold sway, his unimpeachable punk contrariness has won him the trust of ordinary Macedonians. Until the skirmishes on the Kosovan border near Tetovo last month, both main Macedonian communities shared a fierce common pride in being the only former Yugoslav republic in which not a single shot had been fired in anger. The dreamlike Before the Rain, and its powerful appeal for tolerance, was the fairytale all ethnic groups seemed to have taken to heart. New countries need heroes, and Manchevski, the punk who ran away to the US ":as soon as I could":, and who cites the Sex Pistols as his greatest formative influence, was accidentally cast in the role of its chief iconographer. The prodigal son was being handed the mythic glue to hold the nation together - it was as if Malcolm McLaren was being asked to reinvent the monarchy. Dust - in which shifting alliances of Albanians, Bulgarians, Serbs, Turks, Greeks and various brigand bands battle for dominance as Macedonia emerges from five centuries of Ottoman rule - will be watched through that very delicate prism when it first sees the light of day at either the Cannes or the Venice film festivals; both are currently battling for the right to show it first. It is a fair bet that a few shadowy men from the Pentagon and the UN will want an early look, too. If that responsibility weighs heavily on Manchevski, he doesn't show it. Wiry, boyish and as charming as he is intense, even among his own he's a person apart, an effect intensified by a slightly off-centre pupil in one eye. No one knows much about his childhood in Skopje and he likes to keep it that way. His mischievous bluster, though, betrays a certain nervousness. ":I am an outsider. I was never part of any political or cultural establishment, even though in these parts you have to be because social life is so tribal. It's very like Hollywood, I guess. So I haven't had to sell my ass, which makes the government here suspicious of me. All this talk of civil war is crazy and dangerous. I really don't think it can happen. Then again, I said that about Bosnia. Macedonia is not Kosovo, you just can't compare how the Albanians have been treated in both places. I'll let you into a secret. That fighting in Tetovo is all my fault. I bribed them [the Albanian guerrillas] for publicity for the film and they just got a little carried away.": Skopje airport has that uneasy feel of a place just out of earshot of something nasty. The flight from London was full of wary Americans and country casual Brits with Sandhurst accents pretending to be something in the City. A US Chinook helicopter thundered by as soon as we landed, lugging itself over the ammunition and fuel dumps that line the runway and out across the bristling weaponry dug into the fields beyond. It was bound for Kosovo, just beyond the ridge of mountains on the horizon where a low-level war is still raging. Systematic Serb ethnic cleansing of the long-suffering majority Albanian community has given way to slow and but equally cynical creation of an ethnically pure Albanian state. Nato keeps score with impeccable fairness. You can tell how close a country is to going belly-up when everyone with a car becomes a taxi driver. And everyone in the surging throng outside the doors of Skopje airport, except the Albanian women in scarves and ankle-length coats wrestling returning sons to their chests, was a taxi driver. Macedonia has paid a horrific price for allowing itself to be used as Nato's forward base against Milosevic. The blockade of Serbia, its main market, has destroyed its industry and the exodus of 400,000 Kosovan Albanian refugees threatened to upset its already delicate 65/30 ethnic balance between Orthodox Slavs and Muslim Albanians. No wonder, to the horrified hypocrisy of the West, it eventually tried to close the border. Before the Balkan wars of the 1990s it was the second poorest Yugoslav republic after Kosovo, now its unemployment rate is over 50 per cent. The average weekly wage for those lucky enough to still be in work is £25. You can't eat spectacular scenery. With the roads thick with US military convoys and Humbies full of GIs taking their R&R chasing out-of-work Skopje factory girls, it is not hard to see where Manchevski drew the inspiration for Dust, where Fiennes' fire-and-brimstone Arizona preacher hunts down and does battle with his amoral beast of a brother in the middle of someone else's war. Setting the story just as the Ottoman empire collapsed almost overnight and took the most stable, multi-ethnic society in Europe with it, was no accident either. It is from the two, short, messy wars in 1912 and 1913 that the myth of the unruly, ungovernable Balkans largely stems. Manchevski drew on the detailed reports of the Carnegie Commission into the First and Second Balkan wars for much of his material, but it was the far more colourful Confessions of a Macedonian Bandit written by the San Franciscan adventurer Albert Sonnichsen a few years earlier that really fascinated him. ":I became came very conscious of the parallels of Westerners, particularly Americans, getting sucked into local quarrels and wars, almost always without fully understanding what is going on. |It was as if they were trying to work out something in themselves. It is like with some charity workers now, it's all a glorified way of going to the shrink.": Just to reinforce the point, Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, has memorable cameo, being sick over the side of a transatlantic liner. Sonnichsen's photographs of these outlandishly dressed bands of brigands convinced Manchevski he had to shoot the film as a Baklava Western. ":We couldn't use some of the things Sonnichsen described because they were just too fantastic. People would not believe it. The more I saw and read the more I was reminded of the most way-out Mexican Zapatista revolutionaries and bandilleros, it was like they had been shopping in the same boutique.": The violence was another common thread. For when it came to cold calculated cruelty, the sullen cowpokes who people the novels of Cormac McCarthy and the films of Sam Peckinpah scraped the same barrel as the Balkan brigands. ":It is very hard reading the Carnegie Commission reports,": says Manchevski, ":because you realise the violence that went on then is still happening in the Balkans. People were sliced open and their guts used to strangle them. Arms were cut off and then used to beat that person to death, people buried up to their necks and set alight with gasoline. This became the general Western perception of Balkan behaviour that was reinforced by the misconceptions created by writers like Rebecca West (author of the ":definitive": Yugoslav travelogue Black Lamb and Grey Falcon). When you need to exorcise your own demons who assign them to someone else. This was not violence unknown to the West, or indeed in the Old American West, on the contrary the violence in the Balkans was always and still is less efficient.": We joke that if the Germans had been involved there would only have been one Balkan war, little suspecting that last month, when the fighting broke out in the hills above Tetova, a German tank unit which stood idly by would be scathing about the local Macedonia police's half-hearted attempts to mortar the rebels out. Had they sealed the border with Kosovo , the shooting might never have started. Having visited Tetova during fighting, Manchevski, in a typically contrary flourish, said he was intensely proud of the half-arsed way the Albanian gunmen who attacked the town were dealt with. ":If the Macedonians had gone in all guns blazing Hollywood style it would have been a mess. Not one Albanian store window has been smashed during the terrorist raids on Tetovo. There has been no ethnic retaliation, nor escalation and that must be applauded.": Although he sympathises with many of the relatively modest Albanian demands on the recognition of their language and university, he is also angry that ":no Albanian party nor intellectual has issued a clear-cut condemnation": of the violence, which he sees as racist. ":If you treat institutions of law and order as illegitimate by default, you risk turning the place into a Milosevic-style quasi-state. It breeds distrust. When you start using violence you never know where it will end. Even if you qualify it as a fight for human rights. All it takes is one guy to get drunk and go nuts and the whole thing goes up. This whole situation has been escalated, both psychologically and physically by Kosovo. The Albanian gunmen, who mostly come from Kosovo, have got the crazy mistaken impression that the West bombed the Serbs so they could have their pure greater Albanian mega-state. It is a very similar situation to what the US got into with the Taliban in Afghanistan; a text-book example of 'blowback'. The West has created its own little jihad in Kosovo by arming the KLA. Talk of human rights is being used as a very thin veneer for good old-fashioned peasant land-grabbing and redistribution of criminal cartel spheres of influence. The West has a lot of responsibility here that it has not been facing up to.": He was also angry at the ":inflammatory": coverage of the conflict, particularly by the BBC, who he accused of making out that a slide into civil war was almost inevitable when it isn't. Manchevski, it has to be said, is a Slav but even the Albanians in Tetova I spoke to this week, whose attitude to those gunmen in the hills is ambivalent to say the least, agree the time has now come to put away the guns and talk. Arsim Celaj, a student who claims to have been beaten by Macedonian police because he attends the town's ":illegal": Albanian university, said there had to be ":dialogue and compromises. The government has to talk to us. All this has happened because of frustration that nothing was being done for Albanian people. There must be dialogue now not more war.": ":I won't lie to you. It's been hell, but things are at last looking up,": Chris Auty, the film's English co-producer assured me the night I arrived at their base in the dusty provincial town of Prilep. A few hours later Auty, a man of limitless optimism and good grace, was savaged by a mastiff on the doorstep of his hotel. He even managed a toothy smile as he limped, nauseous back onto set the next day at Treskovac after a double tetanus jab. I hadn't the heart to mention rabies. ":Could have been worse,": he sighed. Manchevski could have bitten him. Film-making, particularly in 50 degree heat in awkward, inaccessible locations can be a testy business at the best of times. But Auty, an old Bertloucci hand, and no stranger to controversy having produced David Cronenberg's Crash, does not try to conceal that working with Manchevski, who admits a fondness for lobbing the occasional grenade to liven things up, has made the shoot ":one of life's more interesting experiences":. ":Milcho is Milcho, he's a one-off. I know it all going to be worth it because the guy is a genius, but it's been tough. We have all suffered, but I think he has suffered most, because it means so much to him, and you have to respect that. It's been the most gruelling shoot I've ever been on. In fairness, nature could not have been more cruel, as well as the heat we have had every kind of plague she could have thrown at us.": In another one of those little absurdities that surrounded Dust, and its grim merrygoround of racial conflict, there was more than the odd crackle of ethnic tension on set too. Playing Frisbee during a break in the filming at the monastery with a medieval copper plate a couple of the Macedonian crew members had found among the ancient ruins of the summit, I got of whiff of some simmering discontent among the natives. It was clear the ":imperious": attitude of a few of the British crew called in to straighten things out had not gone down terribly well. Nor were they happy that technicians they felt could have been recruited locally were being flown in from London. Tensions came to a head over the vexed issue of toilet facilities. Just as at Waterloo, I am proud to report that Blighty won the Battle of the Portaloos and British bog standards prevailed. The Western contingent was also a little sniffy about the crumbling of Soviet-era hotel in which they were billeted. My own room, which had a rather fetching little Gaudiesque tower of bird shit on balcony, was fine once you got used to the smell of diesel. Its greatest joy, however, was its socialist share-and-share-alike wardrobes, which opened into next door's closet. Having passed an uneasy night listening to my neighbours have non-stop sex, banging out the complete works of Shakespeare on the headboard in Morse, they invited me through the wardrobe in the morning to join them for a glass of sljivovice (plum brandy). Drago and Maria were married, but not to one another. He was a salesman and she was a friend of someone working on the film. Both were Macedonian Slavs and were keen to share their opinions of their Albanian brethren - lazy, criminal, backward, rich, drug-dealing mafiosi, bent on breeding their way to power was just about the gist of it. Even if there was truth in some of what they said - and there is no denying Macedonia's drug trade has blossomed since the economy collapsed - that sort of paranoia and casual bigotry has a horrible habit of ending in tears. Nor did their belief that Albanians were rolling in dough quite tally with the evidence of my own eyes. The Albanians in the streets of Prilep seemed markedly poorer, and had that look of people used to keeping their heads down. Manchevski warns about not seeing the sties in your own eye, but even he is highly critical of what he calls the ":anachronistic structures": of Albanian life which he blames for allowing ":those men with machine guns in the hills above Tetova to hijack the whole concept of human rights. No one talks about the human rights of Albanian women, the way they are treated. They have absolutely no say, very few go to school, almost none work out of the house, it's like Afghanistan, for Heaven's sake. But you have seen them, in those long coats and scarves in 40-degree heat. When the world feels sorry for the Albanians, I think they should remember their grievances are not that great that they justify going to war. Macedonia is a state based on a proper co-habitation and toleration. The vice-president of parliament is an Albanian for Christ sake and six of the 17 ministers are too, plus deputy ministers of most ministries, the police, the army, a number of ambassadors. Macedonia is a very young country. It is true in the early days it had to strong line of Macedonian nationalism to set itself apart from Serbia, but that nationalism has been reined in now. There are many legitimate issues to be discussed, but what many Macedonians worry about is that when Albanians talk about human rights what they really want is secession. Albanian parties in Macedonia more often identify with ethnic Albanian causes in Kosovo or Albania than with the cause of the Macedonian state. They sit in the government, but act like foreign-state opposition. Either shit or get off the pot. These politicians have to decide if they want to be in this country or not.": And Manchevski is a Macedonian liberal. His views on the gangsterism he sees spreading among rural Albanians, fears even some militant Albanians in Tetova privately share, are equally forthright. ":Too much has been made of this stuff about centuries' old hatreds. At least a part of the shooting is about local strongmen being able to keep their fiefdoms so there is open roads for smuggling, the drug trade and who runs the brothels and gets first go. It is that basic for a lot of these guys with the guns. If there is no structure anymore because everything is going up in smoke then they are the bosses. There is a big problem with crime, drug running and prostitution among the Albanian community and it has got to be faced up to. ":We have this terrible history of land grabbing we have to be wary of. No one mentions the terrible ethnic cleansing carried out by the Albanian Nazi quasi-state in western Macedonia during the war. It was very telling how the president of Albania was one of the first to come out against what was happening in Tetovo, and he basically said, 'We don't support this, wipe them out.' People in Albania don't want this super state nonsense. They know it is stupid.": Back in Tetova, Artan Skendera is getting his breath back after the busiest month of his life. He runs the local Albanian TV station, Art TV, from which most of the pictures of the fighting have been sent. It's been good for business, but it's business he'd rather do without. Artan, as the name of his station suggests, is an idealist, a believer in the power of art to overcome all enmities. He is also a big fan of Manchevski the film-maker if not the proto-politician. ":If everyone in Macedonia was like Manchevski we would have less problems. Before The Rain told the truth about all the peoples of Macedonia. It was very important for all of us, it showed our lives to the world.": Dust too, he hopes, might bring Slavs and Albanians closer again. ":Some things like beauty and art are above nationalism,": he says. It is asking a lot from a piece of entertainment.

Joe Fiennes is having another bad day. While Naomi Campbell grows impatient for his company in London - and the lady is not one for waiting - he is stuck on a scorching hot Balkan mountain top, the air thick with every sort of biting and stinging insect. The brain begins to boil at about 42 degrees celsius (108 fahrenheit) - and, this morning, with forest fires raging on the horizon, the temperature is touching a barely believable 50. Joe won't be getting to London any time soon. Today, though, he gets to give his Australian co-star David Wenham a good kicking. You can hear the dull thud of boot on rib as soon as you leave the shade of the ancient Orthodox monastery of Treskovec in southern Macedonia and snake your way up through the tinder-dry alpine meadow strewn with Byzantine rubble to the baking rock of the summit. Wenham is writhing in the dust, coughing and spluttering, surrounded by a halo of wasps. Fiennes, unshaven, irritable and obviously relishing the prospect of another day stewing in his own sweat, kicks him in the stomach, grinds the heel of his cowboy boot down on Wenham's hand and drawls: ":You never were no good, Luke.": This goes on, with a short break for lunch and an adjustment of Wenham's bandages, from 9am until after 8pm. By then, even Milcho Manchevski (the man who persuaded them to ":come to Macedonia and be in my 'eastern' - it'll be fun":) has had enough. And this was one of the good days on the set of Dust, the first ":baklava western":. Even by the tortuous standards of movie-making, this was a bizarre and horrendous shoot - Apocalypse Now without the luxury of a studio budget. The omens were not good. From day one, the crew began dropping like flies from dysentery and a medical dictionary of equally nasty complaints - even the unit doctor invalided himself out. Then it got weirder. A week before I arrived, as the worst heatwave to hit the Balkans in 30 years added sunstroke to the sick list, a flock of marauding sheep, half-demented with thirst, overran the set. These being Balkan sheep, there were casualties. A few days later, several people were badly stung by thousands of wasps drawn to the watermelons bought to keep the surviving crew from expiring. The swarm was followed by plagues of mosquitoes and horse flies. Then came dark mutterings from the Macedonians on the crew of a government plot. Wasn't it strange how, as the thermometers on set screeched towards 50 degrees celsius, each night on the state TV news the temperature never topped 42 - the level above which a national emergency would have to be declared and all work stop? It was as if the film - a Cain and Abel, id versus ego, parable of two cowboy brothers from the old American west who bring their deadly filial feud to Macedonia when they enlist as mercenaries on opposing sides during the first Balkan war of 1912 - had incurred the wrath of the Almighty. If it sounds like something only Sam Peckinpah might have attempted, you'd be right. But then old Sam always claimed to have the devil on his side. Everything, including Nato, seems to have conspired against Dust and its dramatic historical sweep from the badlands of Arizona to bandit-ravaged turn-of-the-century Bitola, where the young Ataturk fought in vain to keep the Macedonia of his birth under Ottoman control. As final preparations for filming began in the spring of 1999, war broke out in neighbouring Kosovo and frightened the money away. Manchevski's pleas to be allowed to go ahead were drowned out by the roar of American B52s passing overhead on their way to pulverise Pristina. There was one other unquantifiable factor at work here almost as fiery as the weather. For, presiding over this surreal Fitzcarraldo in a huge cartoon stetson hat was the enigmatic figure of Manchevski himself, a former punk from the Macedonian capital of Skopje, who walked off the set of his last film after only a fortnight because he claimed its Hollywood producer thought ":she had a bigger dick than me":. And yes, those immortal words ":He'll never work in this town again": - or ones very like them - were indeed uttered by Laura ":Pretty Woman": Ziskin after that spectacular falling out on the cannibal flick Ravenous. (Tellingly, the crew rebelled against Manchevski's replacement and Ravenous was eventually finished by the British director Antonia Bird, who maintains that its problems were not of Manchevski's making. ":He'd been stitched up big time, in my opinion.":) Even shorn of his green mohican, Manchevski cuts quite a figure. Only someone with a highly developed sense of the ridiculous could stride on to a set in a joke cowboy hat and badass shades, with a vast pashmina shawl draped around his narrow shoulders, and expect to take charge. First impressions, of course, can be very deceptive. Manchevski may have picked up the swagger, and that eccentric dress sense, directing pop videos in America for the likes of Arrested Development, but he is no cocky fool. For he knew there was a lot more than money, or even whether he would be allowed behind a camera again, riding on Dust. ":I spent five and half years sweating blood to make this film,": he says. ":I was making a shit-load of money trying to make studio films, but I just couldn't do it. You can't make good films that mean something by remote control. You couldn't make up what happens in LA, it's beyond satire. Hollywood is full of the most miserable, unhappy people I have ever met - and I'm from the Balkans.": That little contretemps with Ziskin, arguably the most powerful woman in Hollywood, would have probably finished his career had Manchevski not had an Oscar nomination and won the Golden Lion at Venice for Before the Rain, his lyrical debut warning of what might happen if Macedonia followed the rest of the former Yugoslavia over the abyss into war. It is hard to underestimate the effect Before the Rain had on this tiny, fragile and fragmented country of 3m, with no obvious historical or ethnic precedents other than a shared reluctance from its either Slav or Albanian-speaking peoples to throw their lot in with the madhouses of Belgrade or Tirana. Macedonia - the word means ":mixed": - also has Serb, Vlach, Roma and Bulgar minorities, making it in present Balkan terms more a conundrum than a country. In such disputed circumstances, Manchevski has become, unwittingly and unwillingly, more national talisman than mere film-maker. His perfectionism may make him a nightmare to work with at times, but in a country where cliques and political cabals hold sway, his unimpeachable punk contrariness has won him the trust of ordinary Macedonians. Until the skirmishes on the Kosovan border near Tetovo last month, both main Macedonian communities shared a fierce common pride in being the only former Yugoslav republic in which not a single shot had been fired in anger. The dreamlike Before the Rain, and its powerful appeal for tolerance, was the fairytale all ethnic groups seemed to have taken to heart. New countries need heroes, and Manchevski, the punk who ran away to the US ":as soon as I could":, and who cites the Sex Pistols as his greatest formative influence, was accidentally cast in the role of its chief iconographer. The prodigal son was being handed the mythic glue to hold the nation together - it was as if Malcolm McLaren was being asked to reinvent the monarchy. Dust - in which shifting alliances of Albanians, Bulgarians, Serbs, Turks, Greeks and various brigand bands battle for dominance as Macedonia emerges from five centuries of Ottoman rule - will be watched through that very delicate prism when it first sees the light of day at either the Cannes or the Venice film festivals; both are currently battling for the right to show it first. It is a fair bet that a few shadowy men from the Pentagon and the UN will want an early look, too. If that responsibility weighs heavily on Manchevski, he doesn't show it. Wiry, boyish and as charming as he is intense, even among his own he's a person apart, an effect intensified by a slightly off-centre pupil in one eye. No one knows much about his childhood in Skopje and he likes to keep it that way. His mischievous bluster, though, betrays a certain nervousness. ":I am an outsider. I was never part of any political or cultural establishment, even though in these parts you have to be because social life is so tribal. It's very like Hollywood, I guess. So I haven't had to sell my ass, which makes the government here suspicious of me. All this talk of civil war is crazy and dangerous. I really don't think it can happen. Then again, I said that about Bosnia. Macedonia is not Kosovo, you just can't compare how the Albanians have been treated in both places. I'll let you into a secret. That fighting in Tetovo is all my fault. I bribed them [the Albanian guerrillas] for publicity for the film and they just got a little carried away.": Skopje airport has that uneasy feel of a place just out of earshot of something nasty. The flight from London was full of wary Americans and country casual Brits with Sandhurst accents pretending to be something in the City. A US Chinook helicopter thundered by as soon as we landed, lugging itself over the ammunition and fuel dumps that line the runway and out across the bristling weaponry dug into the fields beyond. It was bound for Kosovo, just beyond the ridge of mountains on the horizon where a low-level war is still raging. Systematic Serb ethnic cleansing of the long-suffering majority Albanian community has given way to slow and but equally cynical creation of an ethnically pure Albanian state. Nato keeps score with impeccable fairness. You can tell how close a country is to going belly-up when everyone with a car becomes a taxi driver. And everyone in the surging throng outside the doors of Skopje airport, except the Albanian women in scarves and ankle-length coats wrestling returning sons to their chests, was a taxi driver. Macedonia has paid a horrific price for allowing itself to be used as Nato's forward base against Milosevic. The blockade of Serbia, its main market, has destroyed its industry and the exodus of 400,000 Kosovan Albanian refugees threatened to upset its already delicate 65/30 ethnic balance between Orthodox Slavs and Muslim Albanians. No wonder, to the horrified hypocrisy of the West, it eventually tried to close the border. Before the Balkan wars of the 1990s it was the second poorest Yugoslav republic after Kosovo, now its unemployment rate is over 50 per cent. The average weekly wage for those lucky enough to still be in work is £25. You can't eat spectacular scenery. With the roads thick with US military convoys and Humbies full of GIs taking their R&R chasing out-of-work Skopje factory girls, it is not hard to see where Manchevski drew the inspiration for Dust, where Fiennes' fire-and-brimstone Arizona preacher hunts down and does battle with his amoral beast of a brother in the middle of someone else's war. Setting the story just as the Ottoman empire collapsed almost overnight and took the most stable, multi-ethnic society in Europe with it, was no accident either. It is from the two, short, messy wars in 1912 and 1913 that the myth of the unruly, ungovernable Balkans largely stems. Manchevski drew on the detailed reports of the Carnegie Commission into the First and Second Balkan wars for much of his material, but it was the far more colourful Confessions of a Macedonian Bandit written by the San Franciscan adventurer Albert Sonnichsen a few years earlier that really fascinated him. ":I became came very conscious of the parallels of Westerners, particularly Americans, getting sucked into local quarrels and wars, almost always without fully understanding what is going on. |It was as if they were trying to work out something in themselves. It is like with some charity workers now, it's all a glorified way of going to the shrink.": Just to reinforce the point, Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, has memorable cameo, being sick over the side of a transatlantic liner. Sonnichsen's photographs of these outlandishly dressed bands of brigands convinced Manchevski he had to shoot the film as a Baklava Western. ":We couldn't use some of the things Sonnichsen described because they were just too fantastic. People would not believe it. The more I saw and read the more I was reminded of the most way-out Mexican Zapatista revolutionaries and bandilleros, it was like they had been shopping in the same boutique.": The violence was another common thread. For when it came to cold calculated cruelty, the sullen cowpokes who people the novels of Cormac McCarthy and the films of Sam Peckinpah scraped the same barrel as the Balkan brigands. ":It is very hard reading the Carnegie Commission reports,": says Manchevski, ":because you realise the violence that went on then is still happening in the Balkans. People were sliced open and their guts used to strangle them. Arms were cut off and then used to beat that person to death, people buried up to their necks and set alight with gasoline. This became the general Western perception of Balkan behaviour that was reinforced by the misconceptions created by writers like Rebecca West (author of the ":definitive": Yugoslav travelogue Black Lamb and Grey Falcon). When you need to exorcise your own demons who assign them to someone else. This was not violence unknown to the West, or indeed in the Old American West, on the contrary the violence in the Balkans was always and still is less efficient.": We joke that if the Germans had been involved there would only have been one Balkan war, little suspecting that last month, when the fighting broke out in the hills above Tetova, a German tank unit which stood idly by would be scathing about the local Macedonia police's half-hearted attempts to mortar the rebels out. Had they sealed the border with Kosovo , the shooting might never have started. Having visited Tetova during fighting, Manchevski, in a typically contrary flourish, said he was intensely proud of the half-arsed way the Albanian gunmen who attacked the town were dealt with. ":If the Macedonians had gone in all guns blazing Hollywood style it would have been a mess. Not one Albanian store window has been smashed during the terrorist raids on Tetovo. There has been no ethnic retaliation, nor escalation and that must be applauded.": Although he sympathises with many of the relatively modest Albanian demands on the recognition of their language and university, he is also angry that ":no Albanian party nor intellectual has issued a clear-cut condemnation": of the violence, which he sees as racist. ":If you treat institutions of law and order as illegitimate by default, you risk turning the place into a Milosevic-style quasi-state. It breeds distrust. When you start using violence you never know where it will end. Even if you qualify it as a fight for human rights. All it takes is one guy to get drunk and go nuts and the whole thing goes up. This whole situation has been escalated, both psychologically and physically by Kosovo. The Albanian gunmen, who mostly come from Kosovo, have got the crazy mistaken impression that the West bombed the Serbs so they could have their pure greater Albanian mega-state. It is a very similar situation to what the US got into with the Taliban in Afghanistan; a text-book example of 'blowback'. The West has created its own little jihad in Kosovo by arming the KLA. Talk of human rights is being used as a very thin veneer for good old-fashioned peasant land-grabbing and redistribution of criminal cartel spheres of influence. The West has a lot of responsibility here that it has not been facing up to.": He was also angry at the ":inflammatory": coverage of the conflict, particularly by the BBC, who he accused of making out that a slide into civil war was almost inevitable when it isn't. Manchevski, it has to be said, is a Slav but even the Albanians in Tetova I spoke to this week, whose attitude to those gunmen in the hills is ambivalent to say the least, agree the time has now come to put away the guns and talk. Arsim Celaj, a student who claims to have been beaten by Macedonian police because he attends the town's ":illegal": Albanian university, said there had to be ":dialogue and compromises. The government has to talk to us. All this has happened because of frustration that nothing was being done for Albanian people. There must be dialogue now not more war.": ":I won't lie to you. It's been hell, but things are at last looking up,": Chris Auty, the film's English co-producer assured me the night I arrived at their base in the dusty provincial town of Prilep. A few hours later Auty, a man of limitless optimism and good grace, was savaged by a mastiff on the doorstep of his hotel. He even managed a toothy smile as he limped, nauseous back onto set the next day at Treskovac after a double tetanus jab. I hadn't the heart to mention rabies. ":Could have been worse,": he sighed. Manchevski could have bitten him. Film-making, particularly in 50 degree heat in awkward, inaccessible locations can be a testy business at the best of times. But Auty, an old Bertloucci hand, and no stranger to controversy having produced David Cronenberg's Crash, does not try to conceal that working with Manchevski, who admits a fondness for lobbing the occasional grenade to liven things up, has made the shoot ":one of life's more interesting experiences":. ":Milcho is Milcho, he's a one-off. I know it all going to be worth it because the guy is a genius, but it's been tough. We have all suffered, but I think he has suffered most, because it means so much to him, and you have to respect that. It's been the most gruelling shoot I've ever been on. In fairness, nature could not have been more cruel, as well as the heat we have had every kind of plague she could have thrown at us.": In another one of those little absurdities that surrounded Dust, and its grim merrygoround of racial conflict, there was more than the odd crackle of ethnic tension on set too. Playing Frisbee during a break in the filming at the monastery with a medieval copper plate a couple of the Macedonian crew members had found among the ancient ruins of the summit, I got of whiff of some simmering discontent among the natives. It was clear the ":imperious": attitude of a few of the British crew called in to straighten things out had not gone down terribly well. Nor were they happy that technicians they felt could have been recruited locally were being flown in from London. Tensions came to a head over the vexed issue of toilet facilities. Just as at Waterloo, I am proud to report that Blighty won the Battle of the Portaloos and British bog standards prevailed. The Western contingent was also a little sniffy about the crumbling of Soviet-era hotel in which they were billeted. My own room, which had a rather fetching little Gaudiesque tower of bird shit on balcony, was fine once you got used to the smell of diesel. Its greatest joy, however, was its socialist share-and-share-alike wardrobes, which opened into next door's closet. Having passed an uneasy night listening to my neighbours have non-stop sex, banging out the complete works of Shakespeare on the headboard in Morse, they invited me through the wardrobe in the morning to join them for a glass of sljivovice (plum brandy). Drago and Maria were married, but not to one another. He was a salesman and she was a friend of someone working on the film. Both were Macedonian Slavs and were keen to share their opinions of their Albanian brethren - lazy, criminal, backward, rich, drug-dealing mafiosi, bent on breeding their way to power was just about the gist of it. Even if there was truth in some of what they said - and there is no denying Macedonia's drug trade has blossomed since the economy collapsed - that sort of paranoia and casual bigotry has a horrible habit of ending in tears. Nor did their belief that Albanians were rolling in dough quite tally with the evidence of my own eyes. The Albanians in the streets of Prilep seemed markedly poorer, and had that look of people used to keeping their heads down. Manchevski warns about not seeing the sties in your own eye, but even he is highly critical of what he calls the ":anachronistic structures": of Albanian life which he blames for allowing ":those men with machine guns in the hills above Tetova to hijack the whole concept of human rights. No one talks about the human rights of Albanian women, the way they are treated. They have absolutely no say, very few go to school, almost none work out of the house, it's like Afghanistan, for Heaven's sake. But you have seen them, in those long coats and scarves in 40-degree heat. When the world feels sorry for the Albanians, I think they should remember their grievances are not that great that they justify going to war. Macedonia is a state based on a proper co-habitation and toleration. The vice-president of parliament is an Albanian for Christ sake and six of the 17 ministers are too, plus deputy ministers of most ministries, the police, the army, a number of ambassadors. Macedonia is a very young country. It is true in the early days it had to strong line of Macedonian nationalism to set itself apart from Serbia, but that nationalism has been reined in now. There are many legitimate issues to be discussed, but what many Macedonians worry about is that when Albanians talk about human rights what they really want is secession. Albanian parties in Macedonia more often identify with ethnic Albanian causes in Kosovo or Albania than with the cause of the Macedonian state. They sit in the government, but act like foreign-state opposition. Either shit or get off the pot. These politicians have to decide if they want to be in this country or not.": And Manchevski is a Macedonian liberal. His views on the gangsterism he sees spreading among rural Albanians, fears even some militant Albanians in Tetova privately share, are equally forthright. ":Too much has been made of this stuff about centuries' old hatreds. At least a part of the shooting is about local strongmen being able to keep their fiefdoms so there is open roads for smuggling, the drug trade and who runs the brothels and gets first go. It is that basic for a lot of these guys with the guns. If there is no structure anymore because everything is going up in smoke then they are the bosses. There is a big problem with crime, drug running and prostitution among the Albanian community and it has got to be faced up to. ":We have this terrible history of land grabbing we have to be wary of. No one mentions the terrible ethnic cleansing carried out by the Albanian Nazi quasi-state in western Macedonia during the war. It was very telling how the president of Albania was one of the first to come out against what was happening in Tetovo, and he basically said, 'We don't support this, wipe them out.' People in Albania don't want this super state nonsense. They know it is stupid.": Back in Tetova, Artan Skendera is getting his breath back after the busiest month of his life. He runs the local Albanian TV station, Art TV, from which most of the pictures of the fighting have been sent. It's been good for business, but it's business he'd rather do without. Artan, as the name of his station suggests, is an idealist, a believer in the power of art to overcome all enmities. He is also a big fan of Manchevski the film-maker if not the proto-politician. ":If everyone in Macedonia was like Manchevski we would have less problems. Before The Rain told the truth about all the peoples of Macedonia. It was very important for all of us, it showed our lives to the world.": Dust too, he hopes, might bring Slavs and Albanians closer again. ":Some things like beauty and art are above nationalism,": he says. It is asking a lot from a piece of entertainment.

Back to Milcho Manchevski's home-page.