The Kosovo Explosion

The Dayton Accord failed to include any provisions for Kosovo. The subsequent frustration led many young Albanians to give up on Ibrahim Rugova's nonviolent strategy of building a parallel society which could eventually gain international recognition. In 1997, an Albanian guerilla group, the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), began ambushing police patrols and attacking stations. Serbian security forces responded by sealing off villages and rounding up suspected guerilla collaborators. Reports of torture and "disappearance" of detained Albanians escalated.

Milosevic was then facing the biggest crisis of his career. When his regime refused to recognize local elections for the opposition in November 1996, thousands of protestors took over Belgrade's central square for weeks. The protests were broken by police in January and the opposition coalition splintered, but the regime did finally recognize some opposition electoral victories.

In July 1997, Milosevic, barred by the constitution from running for a third term as Serbian president, had the federal Parliament he controlled elect him president of Yugoslavia. The vote was taken in an atmosphere of terror, with the opposition press closed by decree.

Neighboring Albania had meanwhile descended into chaos. The weak post-Communist government had entered NATO's Partnership for Peace military program, and opened the country to US troops and spy planes. It also promoted unscrupulous pyramid schemes, designed by get-rich-quick outfits to exploit the desperation and ignorance of Europe's poorest, most isolated country. When the pyramids crashed, thousands of Albanians lost their life savings. In March, the country exploded into rebellion. Village clans plundered the armories and seized local control. Thousands of refugees fled across the Adriatic to Italy. In April, a multilateral European intervention force landed, restored a measure of central authority and prepared to oversee new elections.

Many arms plundered from the Albanian military were smuggled across the border to the KLA. Interpol claimed the KLA had also turned to the heroin trade to fund arms purchases. In any case, the rebel group swelled as repression gripped Kosovo.

In February 1998, following a KLA attack on a police patrol which left four officers dead, Serbian police and allied paramilitary groups responded with a new campaign of "ethnic cleansing." By early 1999, hundreds of villages had been torched and a quarter of a million Kosovar Albanians--out of a total population of 1.4 million--displaced. Some fled across the

border to Albania and Macedonia; others hid in Kosovo's mountains.

US envoy Richard Holbrooke secured Milosevic's agreement on a deal calling for an OSCE "verification mission" to monitor the situation on the ground in return for guarantees of Serbian sovereignty over Kosovo. But the violence continued, despite the monitors. International investigators discovered evidence of massacres--which were predictably contested by Serbian authorities.

In February 1999, a new round of US-brokered talks between the Milosevic government and an Albanian team including both Rugova and KLA representatives convened at Rambouillet, France. Milosevic rejected demands for NATO troops to police Kosovo; the Albanians rejected terms mandating a three-year interval before Kosovo could vote for secession. The Albanian team finally gave in and signed the Rambouillet Accords; Milosevic--fearing a backlash from hardliners in his own regime--remained intransigent.

In March, NATO began Operation Allied Force, a sustained bombing campaign of Yugoslavia. Belgrade's police and paramilitary forces responded with Operation Horseshoe, a campaign to finally drive the Albanians from Kosovo altogether. Whole villages fled at gunpoint, families loaded onto tractors. Ultimately, 800,000 settled in massive refugee camps hastily established in Albania and Macedonia. Milosevic was finally accused of war crimes, and ordered to surrender himself to the UN tribunal at The Hague.

In March, NATO began Operation Allied Force, a sustained bombing campaign of Yugoslavia. Belgrade's police and paramilitary forces responded with Operation Horseshoe, a campaign to finally drive the Albanians from Kosovo altogether. Whole villages fled at gunpoint, families loaded onto tractors. Ultimately, 800,000 settled in massive refugee camps hastily established in Albania and Macedonia. Milosevic was finally accused of war crimes, and ordered to surrender himself to the UN tribunal at The Hague.

Despite NATO claims of precision bombing guided by military necessity, civilian targets were widely hit--including bridges, factories, oil refineries, power plants and Belgrade's TV station. After the initial bombings failed to move Milosevic, breaking the will of Serbia's populace became NATO's strategy. In an embarrassing error, a convoy of Albanian refugees was hit. In May, Belgrade's Chinese embassy was destroyed by a NATO missile.  One errant

missile destroyed a civilian passenger train. Another hit a suburban area of Bulgaria. Such "collateral damage" cost perhaps 2,000 lives. NATO forces suffered no casualties, but Yugoslav air defense forces did succeed in downing a US Stealth fighter.

One errant

missile destroyed a civilian passenger train. Another hit a suburban area of Bulgaria. Such "collateral damage" cost perhaps 2,000 lives. NATO forces suffered no casualties, but Yugoslav air defense forces did succeed in downing a US Stealth fighter.

The bombing also unleashed an ecological nightmare. Mercury and PCBs from bombed industrial sites contaminated the Danube, bringing fishing and commerce on the river to a halt. In Pancevo, where a dark cloud from the destroyed petrochemical works enveloped the city, doctors noted a doubling of the miscarriage rate. The use of US anti-tank shells made from depleted uranium sparked concern over the effects of low-level radioactive contamination.

On April 28, the US Congress voted not to either declare war or halt the bombing, ceding authority on the question to the president. While the air assault was overwhelmingly led by the US, it also saw participation by Germany's military in combat operations for the first time since World War II--ironically under a left-coalition government including the Green Party. Greece allowed NATO troops and war material to pass through to Macedonia and Albania, but refused to participate in the air raids. Many NATO countires saw large protests against the bombing.

The bombing ended in late June. Both NATO and Belgrade claimed victory, but in fact both compromised: Milosevic agreed to NATO troops, but the West dropped demands for any moves towards actual independence for Kosovo. The KLA, which had fought Serb forces on the ground throughout the bombing, was to be partially disarmed and converted into a civilian police force. The deal was sanctioned by the UN, which also prepared its own international police force for Kosovo.

As the US, UK, French, Italians and Germans divided Kosovo into occupation zones, Russian troops rushed in from Bosnia to seize Pristina's airport as a bargaining chip. NATO's commander, US Gen. Wesley Clark, wanted to push Russians out, but was overruled by his European coalition partners. Russian troops were allowed into the "peacekeeping force," despite protests from Albanians, who accused Russian mercenaries of participation in Operation Horseshoe.

Kosovo was now a part of Serbia in name only, with power actually divided between NATO and KLA. As Albanian refugees flooded back in, Serb civilians started fleeing towards Belgrade, fearing reprisals. By summer's end, Kosovo's Serb population had been reduced by

two-thirds to 70,000. Towns were divided into Serb and Albanian zones, separated by barbed wire and occupation troops. Both Serbs and Roma, accused of collaborating with the Serbs, were targets of forced evictions, executions and other revenge violence.

As Serb refugees poured in, widespread protests again erupted in Serbia demanding the resignation of Milosevic--in defiance of a state of emergency. Although the opposition is deeply divided, the protest campaign continues as of this writing. There are concerns that Milosevic will foment a new crisis to stem a popular uprising.

top

Dangers of a Wider War

There is much potential for re-escalation of the Balkan crisis, and the presence of foreign troops makes the stakes higher. Many Kosovo Albanians view KLA disarmament or retreat from independence as a capitulation, while Serb hardliners like Seselj accuse Milosevic of selling Kosovo.

Another likely flashpoint is Montenegro, which was bombed by NATO despite being at odds with Belgrade. Montenegro's president, former black marketeer Milo Djukanovic, has support from local Albanians, urban dwellers, and the West, but is opposed by Milosevic's followers. Unwilling to support Serbia's war in Kosovo, Djukanovic threatened to hold a referendum on secession if Montenegro is not granted greater autonomy.

The Kosovo crisis exacerbated divisions in Macedonia. The large Albanian minority there already faced demands for their expulsion and closure of Albanian-language classes at the national university before the country was called upon to host thousands of Albanian refugees. The US has 300 troops in Macedonia--the only US troops under UN command in the world.

A Macedonian crisis could become quickly internationalized, as Serbian, Bulgarian and Greek expansionists all have open designs on the country.

The large Hungarian minority in Serbia's breadbasket of Vojvodina also largely rejected the Kosovo war, and expansionists in Hungary have designs on the region.

Bosnia remains tense and divided, dependent on outside governance and funding. The Muslim-led government in Sarajevo has become more narrowly nationalistic, but has limited control of the country in reality. Karadzic and Mladic remain at large, but have lost control of the Serb Republic to more moderate forces.

In Croatia, efforts by Serb refugees to return to their homes is a source of tension. Tudjman has cancer, and his control is finally eroding due to growing reports of corruption. The Croatian opposition worries that Croatia's continued refusal to abide by international human rights standards, or arrest Croatians wanted by the UN war crimes tribunal, will stall the desired entry into the EU.

In the immediate aftermath of the bombing, Russia conducted its largest military maneuvers since the end of the Cold War. Russian bombers approached Norwegian and Icelandic airspace, and were confronted by NATO fighters. The exercise ended with a "simulated" nuclear strike--a chilling echo of Cold War brinksmanship.

Moscow, facing domestic terrorism and economic collapse, views it as significant that the 1999 bombing campaign began days after NATO, on its 50th anniversary, expanded to include Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland--three former Warsaw Pact members, two of which border the former Soviet Union. Moscow is now waging a counter-insurgency war against Muslim rebels in the Caucasus mountains. The former Soviet republics of Georgia and Azerbaijan, immediately to the south, have established preliminary military-diplomatic links to NATO. In the Central Asian republics of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, NATO is training troops to fight Islamic guerillas in neighboring Tajikistan under the Partnership for Peace program. The Kremlin sees this as an embryonic encirclement of the Caspian Sea, which is eyed by US corporations for major oil development in the 21st century.

top

Never Again?

Wars are often followed by waves of public sentiment that such carnage must never happen again. But wars do happen again, frequently in the same places. The new Balkans wars are usually portrayed in the media as part of a never-ending conflict among ethnic groups. History shows, however, that these conflicts are the result of pressures from more powerful nations and manipulation by the local leaders who do their bidding.

If the international community, either at the level of nation-states or citizen initiatives, truly wants to promote peace, an understanding of Balkan history must inform any action we take. Otherwise, it is likely that the cycles of violent conflict in the region will continue to spiral.

top

November 1999

War At The Crossroads originally appeared in World War 3 Illustrated #28 (P.O. Box 20777, Tompkins Sq. Station, New York, NY 10009).

The Balkan War Resource Group (44 Fifth Ave. #172, Brooklyn, NY 11217) produces educational material for US journalists and activists.

Bill Weinberg is a New York-based journalist who has produced numerous programs on the Balkan wars for WBAI radio. His books are War on the Land: Ecology and Politics in Central America (Zed Books 1991), George Bush: The Super-Spy Drug-Smuggling President (SHADOW Press 1992) and Homage to Chiapas: The New Indigenous Struggles in Mexico (Verso 2000).

Dorie Wilsnack serves on the council of War Resisters International and has worked to support peace groups in the Balkans since 1991. She currently resides in Germany, where she works in the international office of the Balkan Peace Team, a group which monitors the conflict and human rights in the region. She compiled a directory of U.S. organizations doing work in or with the former Yugoslavia: Working for Peace in the Balkans - A Guide to U.S. Organizations.

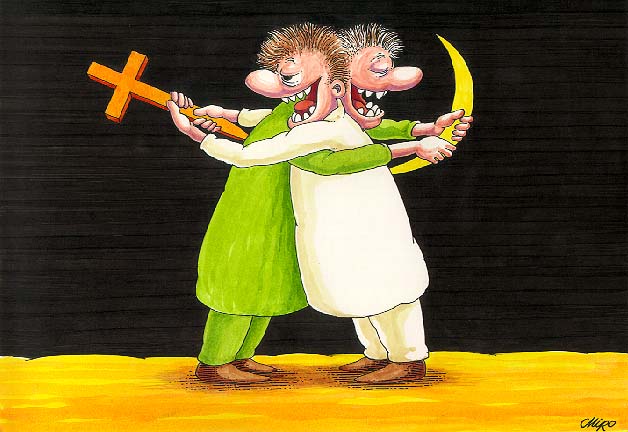

Most of the drawings by Miro Stefanovic.

Code by Ivo Skoric.

top

Why won't the media explain what's behind the upheaval and "ethnic cleansing" in the former Yugoslavia as they justify the deployment of US troops and aerial bombing? Go beyond the media sound bite analysis of "ancient ethnic hatreds" to the real political context for the post-Yugoslav wars. WAR AT THE CROSSROADS is a consice historical primer on the history and roots of the Balkan wars from ancient times to the present, exploring imperialist agendas in the region from the Roman Empire to NATO.

War At The Crossroads

12 pages (book)....$2.00

...is available in bulk from SHADOW Press, P.O. Box 20298, New York, NY 10009. E-mail or send a self-addressed stamped envelope for our latest catalog.

top

The border between the ancient Eastern and Western empires corresponds almost precisely with that of present-day Serbia and Croatia. The power vacuum left by the decline of Rome allowed Croatia and Slovenia in the north and west to maintain a degree of independence and sovereignty--although pressure from the Magyars in Hungary forced them into the influence sphere of the Germanic powers, such as the Frankish empire of Charlemagne. The Serbs, meanwhile, came under Byzantine rule. The neighboring Bulgarian Empire, which included Macedonia, also eventually fell within the Byzantine sphere, as did Montenegro and much of the Dalmatian coast--although the port of Ragusa (today Dubrovnik), a center of trade with the Italian city-states, maintained independence.

The border between the ancient Eastern and Western empires corresponds almost precisely with that of present-day Serbia and Croatia. The power vacuum left by the decline of Rome allowed Croatia and Slovenia in the north and west to maintain a degree of independence and sovereignty--although pressure from the Magyars in Hungary forced them into the influence sphere of the Germanic powers, such as the Frankish empire of Charlemagne. The Serbs, meanwhile, came under Byzantine rule. The neighboring Bulgarian Empire, which included Macedonia, also eventually fell within the Byzantine sphere, as did Montenegro and much of the Dalmatian coast--although the port of Ragusa (today Dubrovnik), a center of trade with the Italian city-states, maintained independence.

After the French Revolution, both nationalism and the idea of South Slav, or "Yugoslav," unity spread in the Balkans. A movement for Serbian independence emerged and, despite violent repression by the

Ottomans, succeeded in bringing about a semi independent Serbian

state by 1830. The following decades saw growing violence. The Turks attempted to crush nationalist movements in Macedonia and to take Montenegro, which maintained a precarious independence. Christian peasants revolted against the Ottomans in Bosnia, and were aided by Serbia and Austria. Bosnia was occupied by Austria in 1878 and formally annexed in 1908.

After the French Revolution, both nationalism and the idea of South Slav, or "Yugoslav," unity spread in the Balkans. A movement for Serbian independence emerged and, despite violent repression by the

Ottomans, succeeded in bringing about a semi independent Serbian

state by 1830. The following decades saw growing violence. The Turks attempted to crush nationalist movements in Macedonia and to take Montenegro, which maintained a precarious independence. Christian peasants revolted against the Ottomans in Bosnia, and were aided by Serbia and Austria. Bosnia was occupied by Austria in 1878 and formally annexed in 1908.

The victorious Allies drew a new

The victorious Allies drew a new  The fascist powers dismantled Yugoslavia. The German occupation ruled Serbia with collaborationist elements of the old regime. A pro-Nazi "independent" Croatian state, including Bosnia, was established under the Ustashe. Italy, which had seized Albania in 1939, occupied Dalmatia and Montenegro, and divided Slovenia with Germany. Most of Kosovo was annexed to Italian-occupied Albania. Hungary took much of Vojvodina, while Bulgaria annexed Macedonia.

The fascist powers dismantled Yugoslavia. The German occupation ruled Serbia with collaborationist elements of the old regime. A pro-Nazi "independent" Croatian state, including Bosnia, was established under the Ustashe. Italy, which had seized Albania in 1939, occupied Dalmatia and Montenegro, and divided Slovenia with Germany. Most of Kosovo was annexed to Italian-occupied Albania. Hungary took much of Vojvodina, while Bulgaria annexed Macedonia. Tito established the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, consisting of six republics (Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia, Macedonia and Montenegro) and two autonomous regions within Serbia (Vojvodina and Kosovo). Not only was defeated Italy forced to cede its claims to Dalmatian territory, but the Italian peninsula of Istria was liberated from Mussolini's rule by Tito's Partisans, and annexed to Croatia. Tito even claimed the Italian city of Trieste, but backed down after sparking a post-war crisis with the West.

Tito established the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, consisting of six republics (Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia, Macedonia and Montenegro) and two autonomous regions within Serbia (Vojvodina and Kosovo). Not only was defeated Italy forced to cede its claims to Dalmatian territory, but the Italian peninsula of Istria was liberated from Mussolini's rule by Tito's Partisans, and annexed to Croatia. Tito even claimed the Italian city of Trieste, but backed down after sparking a post-war crisis with the West.  Tito's system of "self-management" incorporated certain capitalist elements and allowed for a larger degree of autonomy in the industrial sector than in most Communist states. International capital was obtained for the development of heavy industry, especially metallurgy, in Croatia and Slovenia. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) loaned heavily in the 1960s. In the effort to transform a peasant economy into an industrial power, Yugoslavia racked up a $20 billion foreign debt--a figure comparable to many Third World nations.

Tito's system of "self-management" incorporated certain capitalist elements and allowed for a larger degree of autonomy in the industrial sector than in most Communist states. International capital was obtained for the development of heavy industry, especially metallurgy, in Croatia and Slovenia. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) loaned heavily in the 1960s. In the effort to transform a peasant economy into an industrial power, Yugoslavia racked up a $20 billion foreign debt--a figure comparable to many Third World nations.  Albanian teachers and government workers in

Albanian teachers and government workers in  By April, fighting in Bosnia had begun. With support from Serbia, Bosnian Serbs formed their own "Serb Republic" and military under the leadership of poet and psychiatrist Radovan Karadzic. Karadzic's forces sought to cut a corridor though northern Bosnia to connect Serbia with the Serb-controlled areas of Croatia. They attempted to create ethnically homogeneous zones, eventually gaining control of some 70% of Bosnian territory. The

By April, fighting in Bosnia had begun. With support from Serbia, Bosnian Serbs formed their own "Serb Republic" and military under the leadership of poet and psychiatrist Radovan Karadzic. Karadzic's forces sought to cut a corridor though northern Bosnia to connect Serbia with the Serb-controlled areas of Croatia. They attempted to create ethnically homogeneous zones, eventually gaining control of some 70% of Bosnian territory. The  In May 1995, Croatian forces took the Serb-held Western Slavonia enclave, sending Serb refugees fleeing into Serb-held Bosnia.

In May 1995, Croatian forces took the Serb-held Western Slavonia enclave, sending Serb refugees fleeing into Serb-held Bosnia.  Under heavy pressure, the Bosnian Serbs agreed to be represented in Dayton by Milosevic, who suddenly took on the mantle of "peacemaker." This finally brought the lifting of economic sanctions against Serbia.

Under heavy pressure, the Bosnian Serbs agreed to be represented in Dayton by Milosevic, who suddenly took on the mantle of "peacemaker." This finally brought the lifting of economic sanctions against Serbia.  In March, NATO began Operation Allied Force, a sustained bombing campaign of Yugoslavia. Belgrade's police and paramilitary forces responded with Operation Horseshoe, a campaign to finally drive the Albanians from Kosovo altogether. Whole villages fled at gunpoint, families loaded onto tractors. Ultimately, 800,000 settled in massive

In March, NATO began Operation Allied Force, a sustained bombing campaign of Yugoslavia. Belgrade's police and paramilitary forces responded with Operation Horseshoe, a campaign to finally drive the Albanians from Kosovo altogether. Whole villages fled at gunpoint, families loaded onto tractors. Ultimately, 800,000 settled in massive  One errant

missile destroyed a civilian passenger train. Another hit a suburban area of Bulgaria. Such "collateral damage" cost perhaps 2,000 lives. NATO forces suffered no casualties, but Yugoslav air defense forces did succeed in downing a US Stealth fighter.

One errant

missile destroyed a civilian passenger train. Another hit a suburban area of Bulgaria. Such "collateral damage" cost perhaps 2,000 lives. NATO forces suffered no casualties, but Yugoslav air defense forces did succeed in downing a US Stealth fighter.